Art and Philosophy in Programming

If art does not console, and if philosophy does not teach, then what are they for?

I think as programmers, we can learn a whole lot from these things. Not just on how to be wiser people, but apply it in our day-to-day at the office and with our work. For that, let’s walk with two pieces: a painting by Vermeer and a philosophical thought experiment by Plato.

The Milkmaid

This is The Milkmaid by Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer:

You may have seen this painting before—it’s considered one of the great Dutch paintings.

What do you feel? Maybe warmth, or peace? Perhaps a sense of solitude, a steadfastness.

Here is an ordinary peasant pouring milk. The humblest of morning tasks. But look at her! Look at her peace, her pride, her poise. She is satisfied in the work itself. Her mind is not bewildered with what others think of her. She is, as is the popular term today, “in the flow.”

But have you ever wondered why Vermeer bothered to paint such an ordinary woman doing such an ordinary task? Surely he should have spent his time on grander projects that would have pleased the people and brought him wealth and fame. Instead, Vermeer died poor and unknown. So why did he paint this?

Because he wanted to show us something.

Through canvas and through death, Vermeer reaches out to us to say that a person’s work, however small or humble, has an intrinsic value greater than what we may see.

Vermeer tells us that whatever work we do, however minute or hidden, is valuable in itself, and that its value is not derived off how much “utility” it brings into society, or on what the market pays. Instead, the value is based off the intrinsic value of the person doing the work.

This idea is deeply Christian. If we are made in God’s image (that is, a bearer of the character and quality of God himself), then whether we are milkmaid, programmer or president, we are doing a work that God has deemed worthy. Jesus, after all, was a struggling carpenter, and Peter an illiterate fisherman.

What does this mean for us today?

I’m prone to judge people by their work, and perhaps you find this fault in yourself too. But Vermeer teaches us to undo this. As programmers, we can learn to value the work of our counterparts. We can learn to see the intrinsic value of the work done by our product managers, our marketing team, the delivery guy.

This does not excuse lazy work, but it invigorates respect and appreciation of others. If we can learn to do that, then we have learned from Vermeer.

Allegory of the Cave

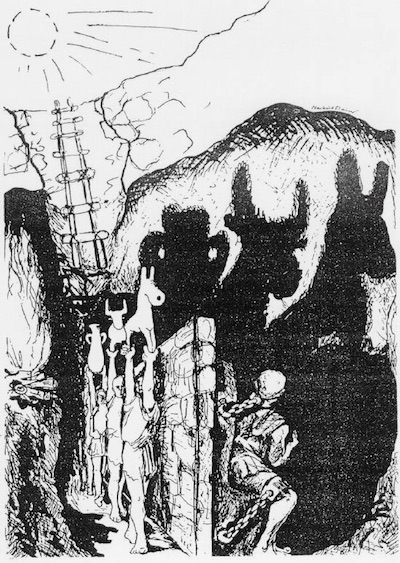

In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, we have a thought experiment.

You are a prisoner chained in a dark cave since birth. You face a wall, and the guards cast shadows of puppets on the wall with fire. The sounds from the guards echo off the wall, making you believe that the shadows are alive.

After decades of imprisonment and watching the living, talking shadows, the guards release you. You turn around and the light of the fire blind your eyes, and the shadows disappear. You are then brought into the day at noon, where there are no shadows. Would you prefer this new world, or the old?

Plato believed that this prisoner would hate the new world, for all he knew was the cave and the shadows. To him, realty is ugly and false, and he would retreat to the cave.

But as the sun begins to set, the prisoner learns how the light casts shadows on objects. He realizes that those shadows were an illusion. He begins, in other words, to understand from first principles of how things work.

From this, I wonder if we all have our caves: ideas and assumptions that we run from because we want what we feel and prefer to be true. We hate the sun not because of the sun, but because of our ignorance and fear.

But if we observe and think from first principles, if we examine how the shadows are created, if we begin to think not in terms of what we’d prefer, either to protect or promote ourselves, but desiring truth above comfort, then we are learning to leave our caves.

In programming, ideas are thrown around us all the time. We learn to put filters and make quick judgements on what is good and bad. I think that’s often necessary; none of us have the time to thoroughly examine every new thing. But I wonder if we often miss out because we prefer the shadows to the real thing.

There are two ways we can be at fault here.

First, can we be too quick to accept the next new framework/language as the next-best-thing ever, simply because everyone else is saying it. We use it because everyone else is doing it, instead of actually understanding why it’s good, or how it’s built.

I hate database websites. They promise all three of CAP or whatever, and globally scalable, yet I say: show me the meat. I don’t remember who said this, but I remember the idea: I don’t want the UML diagrams. Just tell me the table schemas and I will understand the rest.

We must learn to understand from first principles, from the buildings blocks themselves. We need to see the trick behind the flash and bang. We must get away from the marketing page, and look for the meaty documentation. Often we’ll need to read the source code.

On the other hand, we can be too quick to dismiss ideas as bad without giving it a second of thought. This too is a problem: you’ll be stuck in your ancient ways (hey, there are many ancient things that are wonderful and should not be changed; see Vermeer and Plato) and miss out on new advances.

Why do we do this? Fundamentally I think it is the same reason: we prefer the comfort of what we know, damn the truth.

If we have learned from Plato, then our answer is not to readily accept everything as truth, nor to dismiss everything as false. Instead, we must learn to examine critically from the building blocks. That is, we must learn to truly understand.

The return to the cave

In Plato’s cave, the prisoner eventually goes back into the cave. Not because he prefers the chains, but because he pities the other prisoners and wants to free them. But having been accustomed to the light, he stumbles blind into the cave. The other prisoners observe that the outside world has blinded him and, according to Plato, ignore the free man’s pleading and refuse to leave. The desire for comfort, once more, overwhelms truth.

What we can take away from this is how we communicate new ideas is important.

I will use Elixir as an example, because it’s been #1 on HN for 30 days straight and has been the talk of many of my co-workers. Say you’re convinced Elixir is the next best thing. Well, I will not believe you, because I like my languages. And I have better things to do. What convinces would not be, “hey check out this blog post just 10 lines of Elixir for a Slack clone with 2 billion concurrent connections. And if things fail you just don’t worry and it auto-restarts and hypervisor and it works great. And WhatsApp uses Elixir—I mean Erlang—they have 8 billion users last I check.”

That is the argument of the stumbling, blind man trying to save his fellow prisoners. I would rather die in the cave.

What I need is a demonstration of how the shadows are created, how Erlang compares to other runtimes, how the scheduler works, and what “10 trillion threads” actually mean. I want to know what new problems may arise, what the tradeoffs are.

Sometimes all this information is unavailable. Projects like to hide these away as “internal implementation details.” This is out of good intention, but is wrong. To hide the details is to become the freed prisoner that refuses to help the other prisoners, fearing that they’d prefer their dying comfort.

Conclusion

There are things we can learn from the old masters. Like all great ideas, theirs are universal; sometimes comforting, often humbling. From Vermeer we learn that the value of one’s work—indeed, one’s identity—is not rooted in market or societal forces, but in your sacrosanct value as a human being. From Plato we learn the power of understanding from first principles, and the dangers of preferring comfort over truth.

I hope I don’t sound like I’m lecturing. I’d rather let masters lecture. We can all learn from them.